China's Minimal Deterrent

Nuclear breakout and the relationship between nuclear doctrine, posture, and capabilities.

Preamble

This paper was written in 2015; it is dated, and the salient point is not the predictions, which have come to take shape in some form or another, but the relationship between nuclear capabilities, doctrine, and posture, which was very much not the conventional wisdom at the time.Much of the language reflects the information space of the time — China was not considered a great power, and the discourse centred around a regional balancer role. “Great power and/or hegemonic ambitions” as a possibility was overshadowed by “peaceful rise” discourse, which seems unthinkable today.

What’s also striking is the speed and scale at which the situation has changed. In 2015, China’s rural regions were remote, lacked connectivity ,and the PRC was not mechanised or even fully motorised. The relationship between China and Russia has reversed in recent years, with the former becoming the technology provider and benefactor. The size of the Chinese arsenal has nearly tripled to an estimated 600+ warheads over the last decade, with estimations that it’ll grow to 1,000+ by decade’s end. In 2025, the US National Security Strategy document qualified the PRC as a peer competitor.

This paper should stand on its own, and serves as a segue for a retrospective that I am writing. This has been edited for typos, grammar, and presentation, but is otherwise unchanged.

What leads a state to decide on employing a doctrine of assured retaliation (minimal deterrence) vis-à-vis sufficient deterrence, or overwhelming retaliation/mutually assured destruction? Are a state’s nuclear capabilities limited by its doctrine, as conventional wisdom perhaps holds? Or is a state’s nuclear doctrine decided upon as a result of its extant capabilities?

I propose the latter hypothesis, that a given state’s nuclear capabilities shape its doctrine, and that the nuclear capabilities of a state are, in turn, dependent on several factors, including political considerations: that is to say, political priorities, foreign policy ambitions, its positioning as a status quo or revisionist power, political or strategic culture, as well as what the likely political implications and reactions to a state’s nuclear program are anticipated to be. Equally important are physical limitations; a state’s ability to develop a nuclear arsenal may be hobbled by certain constraints imposed by geography and industrial capabilities (not everyone can build everything, nor does every state have the same priorities), and finally, military capabilities and level of technology. In brief, official doctrine can be interpreted as what a state says, but may not be what a state does or intends to do — it is merely a reflection of what a state is currently able to do.

The logically inverse hypothesis, which appears to be the conventional wisdom on the matter, is that a state’s capabilities are not entirely relevant to the formation of its nuclear strategy, and there are certainly examples of states that likely can field a large nuclear arsenal but choose not to. In brief, a state does not develop strategic nuclear capabilities beyond its doctrine, and this can certainly be true; however, I argue that it makes certain assumptions that don’t universally hold.

A State’s declarative doctrine is largely meaningless and cannot be taken as is on its own. The underlying logic of this claim plays heavily on the theory of credible deterrence. A state that espouses a doctrine of overwhelming retaliation or mutually assured destruction, but does not possess the delivery systems and warheads, nor the capability to build them, lags in the required technology, and does not have the surrounding military and industrial infrastructure to sustain and support a large arsenal has no credibility. It may claim to employ a doctrine of overwhelming retaliation, but it cannot deliver on that threat. Similarly, it is difficult to believe a state espousing a doctrine of minimal deterrence when it possesses a full nuclear triad, a large arsenal, advanced delivery systems, and an aggressive foreign policy that suggests an actual position that differs from the one declared.

It is important to analyse the political inclination of a state. Is it a status quo power? Who are its allies? Can it rely on a greater power’s nuclear umbrella? Is it aspiring to rise to great power status itself? What are its rivals doing in terms of nuclear programs? A state that can reliably count on its allies’ nuclear umbrella as a deterrent does not tend to require a large arsenal, nor even its own deterrent. A revisionist power vying for great power or (regional) hegemonic status, however, cannot politically rely on a nuclear umbrella; it would suggest acknowledgement that the possessor of the umbrella is a greater power and a certain, even if minimal, degree of subservience. The deployment of defence systems that weaken a state’s deterrent credibility also requires a response, likely in the form of an increased arsenal and modernised capabilities. The retention of a minimal doctrine in the face of mounting defences suggests an inability, rather than a doctrinal unwillingness to develop an appropriate response — this logic, of course, relies on neorealist assumptions of relative power and of survival being the ultimate objective of a state, as a rational actor, within a Darwinian international system. Equally important, how are a state’s neighbours and rivals likely to react to an obvious, large-scale nuclear build-up? While a state vying for great power status must be able to deter other great powers, it may also wish to avoid a classical security dilemma and the accompanying (overt) arms race.

Geography matters. It limits development. If a state possesses indigenous access to fissile materials, can it otherwise procure them from elsewhere? Does it have places to hide, or increase the survivability of its land-based delivery systems, or the infrastructure (which is, in turn, limited by and built around geographical features)? A mountainous state with poorly developed road and rail connectivity may be unable to leverage its remote regions for this purpose. Can it spread out its forces to increase survivability and second-strike capability? Does a state have open access to oceans or deep, remote littoral waters in which to hide its undersea deterrent?

Economy and industry also matter. Does a state have the technology necessary to develop a credible deterrent beyond what it already possesses? Can a state afford this development, and does it have the capability to build the requisite delivery systems indigenously? How healthy is its military-industrial complex, if it even has one? Can a state realistically sustain a larger arsenal, especially in the case of developing nations, and where does the expansion of its nuclear program fit on its list of development priorities?

Finally, what is the state’s perception of nuclear weapons? Do they have a use? Are they used purely to not be used (deterrence), or do they carry additional uses? Additionally, there is the matter of historical precedence; which extant nuclear power is the state in question most similar to, and as such, is most likely to seek to emulate?

These factors will be analysed in the context of the People’s Republic of China, whose historical use of minimal deterrence has puzzled many. It will also be briefly compared to other nuclear powers to ascertain which it is most similar to and which path it is most likely to follow. The major caveat in this exercise is that not much is known about China’s nuclear program (by design), and much of what is, is based on speculation.

What is the People’s Republic of China’s nuclear doctrine?

China’s nuclear program has its origins in the Taiwan Straits Crisis (1954-55, 1958) when Mao realised that China could not rely on the Soviet nuclear umbrella, as Moscow was not willing to escalate to a nuclear exchange with the United States for the sake of Chinese interests. It was reasoned, therefore, that the PRC must develop its own nuclear program.

During the Mao period, and after the Sino-Soviet Split, the main operational doctrine of People’s War was given a nuclear aspect, centred around the use of atomic demolition munitions planted throughout the routes of advance, which were most likely to be taken by Soviet armour divisions (Bannerjee, 2010, p.351). China claims to pursue a defensive policy aimed at deterring the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons against China. Beijing’s declared position is also one of no first use under any circumstances, never threatening the use of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states, and a firm commitment to the prohibition of nuclear arms (Banerjee, 2010, pp.351-52).

This is perhaps best exemplified by the oft-cited address to the Central Military Commission in July of 2000 by Jiang Zemin, which outlines the “five musts” of Chinese nuclear weapons (Banerjee, 2010, p.352):

”China must own strategic nuclear weapons of a definite quality and quantity in order to ensure national security:”“China must guarantee the safety of strategic nuclear bases and prevent against the loss of combat effectiveness from attacks and destruction by hostile countries;”

“China must ensure that its strategic nuclear weapons are at a high degree of war preparedness;”

“When an aggressor launches a nuclear attack against China, China must be able to launch nuclear counterattack and nuclear re-attack against the aggressor.”

“China must pay attention to the global situation of strategic balance and stability and, when there are changes in the situation, adjust its strategic nuclear weapon development strategy in a timely manner.”

Such an address gives the impression of a defensive policy, but allows leeway for Beijing to act differently in the midst of a real nuclear crisis (Banerjee, 2010, p.353). However, there is nothing specific to a minimal deterrence doctrine contained within those five musts; they are transposable to doctrines of sufficient or limited deterrence as well as doctrines of overwhelming retaliation and mutually assured destruction. It’s unmistakably realist in nature, flexible, and can be read as the Chinese nuclear program being conditional on the retention of the status quo, while it isn’t said explicitly, it can be interpreted as being implied that Beijing reserves the right to expand its arsenal and deterrent capability as it sees fit, contingent on the posture of its rivals.

This is an interpretation corroborated by other analyses, particularly in relation to the American Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) deployments, and the general tone of Sino-American relations, which have been described as mutually ambivalent (Yoshihara, 2008, p.38) as key triggers to Chinese nuclear expansion. Moreover, while the five musts do not explicitly call for first use, they do not expressly disallow it, either.

To wit, in July of 2005, Major General Zhu Chenghu declared to foreign press that “if the Americans draw their missiles and position-guided ammunition onto the target zone on China’s territory, I think we will have to respond with nuclear weapons”. It is unclear if this refers to a change in doctrine and capabilities or to actual nuclear strikes. Chenghu also argues that were the PRC to be faced with defeat in a conventional conflict over Taiwan, it would be forced to launch nuclear attacks on American cities (Yoshihara, 2008, p.37). This begs the question: Is the conventional interpretation of China’s doctrine as minimalist and defensive accurate? These statements indicate Beijing’s willingness to resort to nuclear first-use to protect its national interests, under certain conditions, and, once again, imply that its current nuclear configuration is conditional. Shen Dingly has also stated that if Taiwan were to take the opportunity to declare de jure independence, China would indeed have to exercise its nuclear option (Yoshihara, 2008, p.37). This is a considerable departure from the use of a nuclear program as a nuclear deterrent, and should perhaps be considered in the calculus of ascertaining Chinese nuclear doctrine and posture. It should be considered, perhaps, that Beijing does not share the Western perception of the disutility of nuclear weapons (used only to deter their use), and perhaps, instead, sees its arsenal as a tool of coercion (Tkacik, 201,4 p.162).

Conversely, Beijing has been prone to entering various binding agreements vis-à-vis arms control and bans on nuclear testing (Bleek, 2004, p.1), sending a conflicting message. Though this is likely intentional on the part of China, which is known to deliberately be the least transparent of declared nuclear powers (Bleek, 2004, p.1), and has traditionally placed significant emphasis on secrecy and deception regarding its capabilities (Bleek, 2004, p.1). It is suggested that nuclear ambiguity is perhaps an optimal strategy given the overwhelmingly vast disparity between the known capabilities of the People’s Republic and those of the Russian Federation and the United States (Bleek, 200,4 p.1). To this end, Deng Xiaoping has said that Beijing just allows others to guess, and that the act of guessing, uncertainty is its own form of deterrent, suggesting that not knowing the absolute numbers impairs a rival’s confidence in its ability to deprive Beijing of its retaliatory capability (Bleek, 2004, p.2).

It is suggested that Chinese doctrinal issues are tightly intertwined with the modernisation of Chinese forces, perhaps indicating that declared doctrine changes as their corresponding capabilities change. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists points out that Chinese national defence was ranked behind agriculture, industry, and science and technology, that is to say, last among the priorities of modernisation. They also offer that China lagged far behind the soviet and American programs due to its adherence to Maoist people’s war doctrine and guerrilla principles, and that there has already been a significant internal doctrinal change from deterrence by mounting costs via the denial of ultimate victory, to one of deterrence by threat of retaliation (Simon, 1988, p.46). Given the statements by military officials, it can be assumed that another such change may be on the horizon.

What are China’s nuclear capabilities?

There is little concrete information available about the precise numbers when it comes to China’s nuclear arsenal, as evidenced by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ annual reports on Chinese nuclear forces, nevertheless, the 2015 report states that China is the only one of the original declared nuclear powers to be quantitatively increasing the size of its arsenal (Kistensen, 2015 p.77), from 200 deployed warheads in 2006 (Jristensen, 2006 p.62) to 260 in 2015 (Kristensen, 2015 p.78). While in absolute terms, this may not seem like much, in relative terms, an expansion of 30% over nine years is substantial; in terms of percentages, it is comparable to Cold War expansions of the two superpowers. This is a period where the United States and Russian Federation have reduced their respective stockpiles by a similar margin (Kristensen, 2010, pp.81-2). Over the same period, China has increased its stockpile of long-range nuclear missiles capable of reaching the United States from ~20 to ~65, and its Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBM) stockpile from 12 to 48 with the introduction of the Jin-class SSBN, and increases of 300% and 400%, respectively.

PLAN Type 094 Jin-class SSBN (scmp.com)

The bulk of China’s land-based deterrent consists of relatively inaccurate delivery systems and must therefore be mounted with large, multi-megaton warheads, making the use of MIRVs impractical. The missiles are liquid, rather than solid-fuel, extending firing time, rendering a launch on warning or launch while under attack posture impractical. Their survivability has been increased by storing them in underground caves, separate from their warheads, and erecting empty decoy silos, which is consistent with a minimal deterrence approach. However, Beijing’s considerable effort in developing non-strategic nuclear assets which may be used in counterforce roles against US positions in Asia-Pacific, cannot be considered a minimal approach (Bleek, 2004, p.4).

A theory has been put forward that China’s nuclear forces can be viewed as multi-tiered, with strategic forces being positioned as a second-strike minimal deterrent, and non-strategic assets geared for a more offensive, albeit limited manner (Bleek, 2004, p.4). It is posited that the inaccuracy of China’s strategic assets is the result of technological limitations, rather than by design or due to doctrinal constraints. This is perhaps due to the visibility of ICBMs, and the tendency of foreign media to focus on them at the expense of hundreds of delivery systems that comprise the naval and aerial components of the Chinese arsenal (Bleek, 2004, p.5). The small size of its most visible nuclear assets has spared China a costly arms race (Weitz, 2015) while allowing it to beef up its strategic forces at its leisure. That all being said, the aerial component of the triad is centred on the H-6, introduced in 1959, a derivative of the long obsolete Soviet Tu-16 “Badger” supplemented by nuclear-capable Su-30 fighter bombers purchased from the Russian Federation, indicating an inability on China’s part to produce its own indigenous strategic bombers. Beijing’s reliance on Russian IL-76 aircraft as its main military transport and modified versions of the same for AWACS suggests an incapacity to build indigenous wide-body military aircraft in general. The main emphasis seems to be placed on the development of the Jin-class ballistic missile submarine.

Some analysts argue that China’s large stockpiles of fissile material, the acquisition of which tends to be the most significant and challenging step in the development of nuclear weapons, allow for Beijing to increase the size of its arsenal several times over, and that its seeming reluctance to do so signifies doctrinal constraints (Bleek, 2008, p.4). This stance, however, ignores the significant build-up (in relative terms) mentioned above. It also assumes a utility in developing large quantities of arguably ineffective assets. In brief, China could double or triple the number of land-based warheads it currently has deployed, but is there a point, given how far behind other great powers it lags? It is also argued that the development of the Chinese space program refutes any argument of technological limitations or inadequacies (Bleek, 200,8 p.4). However, this argument makes a false equivocation between space rockets and nuclear delivery systems. It can equally be argued that if technology were not a limiting factor, then China would have solid-fuel delivery systems and miniaturised, MIRV-capable warheads, neither of which is strictly needed in the context of a space program.

China’s booming economy is also cited as an indicator of doctrinal constraints on its nuclear forces structure (Bleek, 2008, p.4), but one cannot simply buy industrial capacity and know-how. In fact, its booming economy may be a factor in the slow modernisation of China’s nuclear forces, as mentioned earlier, national defence (and therefore nuclear forces) were ranked lowest on the list of modernisation priorities, after economic, industrial, and technological priorities. The argument is a little backwards, in that while a strong economy and technological research and development certainly facilitate the development of an advanced deterrent, China was not always in this position. Looking at its current position to explain its historical posture is spurious at best. China is in a strong position now, having invested heavily in its technology sector, and as such, has expanded its nuclear arsenal considerably over the last decade, as well as modernised its SSBN fleet — though not the ground and aerial arms of the triad.

Furthermore, these arguments don’t take into account the structural realities of the Chinese military industrial complex. For instance, in 1980, 20% of the Chinese defence industry production consisted of manufacturing civilian products. This number soared to 30% by 1990. Some suggest that the limited liberalisation of the Chinese economy has rendered some “infatuated” with the profit potential of targeting the consumer market, and that it may prove difficult to re-focus that production capacity toward military aims. Additionally, the third line of defence and research installations were moved out of major cities and to remote, rural areas to increase their survivability, consuming a non-trivial amount of investment capital, as well as rendering these facilities vulnerable to transportation and communication bottlenecks, making it difficult and costly to reintegrate them into the economic mainstream (Kristensen, 1988, p.47). It is reasonable to argue that China’s strategic forces and military industrial complex were not immediately reintegrated into the economic mainstream and did not fully benefit from China’s vastly increased economic clout until well into China’s economic boom. Once again, and this cannot be restated enough, national defence was, after all, listed behind everything else in the modernisation roadmap. There is evidence to suggest that a number of these technological, industrial, and economic limitations are being addressed and overcome, e.g. the SSBN and stealth fighter programs, as well as the development of the MIRV-capable delivery platforms, though not completely, e.g. the continued reliance on the Tu-16-derived H-6 as the core of its aerial deterrent.

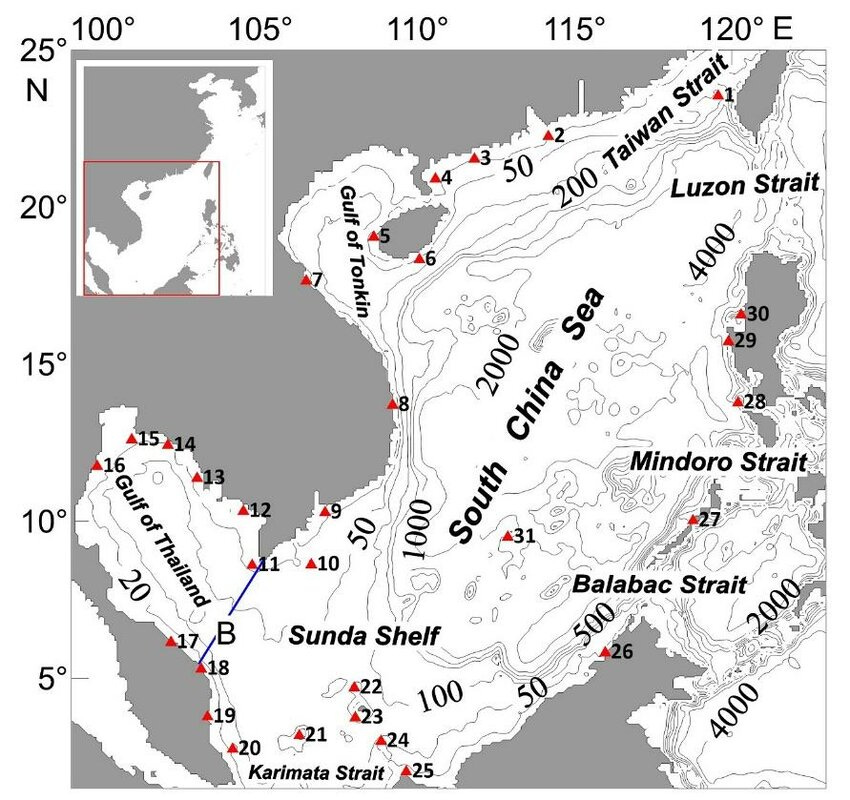

There are also geographic considerations to take into account. On one hand, China has leveraged its vast and mountainous terrain to increase the survivability of its land-based forces, which have historically, and continue to (insofar as we know) make up the bulk of the Chinese arsenal. There are, however, less beneficial considerations, for instance, the relative shallowness of China’s littoral waters, and the lack of clear, unrestricted access to the Pacific, which would render its relatively noisy (relative to modern, or even Cold War era Soviet/Russian/Indian, American/British, and French counterparts). SSBN bastions are vulnerable without a safe haven. To this end, Beijing appears to be attempting to alter its geographical constraints to a more favourable configuration, judging by its assertive policy in the South China Sea (SCS), regarding its expanded exclusive economic zone and “planting” of artificial islands. Breaching the first island chain would, to an extent, grant Beijing the unfettered access to the Pacific depths that it previously lacked

South China Sea depth map in meters (https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-South-China-Sea-and-its-neighbouring-area-The-contours-show-the-water-depth_fig4_367117621)

This is a stark distinction between China, which has historically neglected its undersea deterrent — other than Soviet-procured Golf-class subs, and the one Xia-class — compared to the other nuclear powers. France and England had unrestricted access to the ocean, which they patrol routinely. India’s lone Akula-class, leased from the Russian Federation, patrols the Indian Ocean in relative safety. The United States has unfettered access to two oceans, and the Soviet Union/Russian Federation have leveraged the safe, remote depths of the Sea of Okhotsk and the Arctic Ocean. China’s lack of such favourable geographic conditions may explain its neglected SSBN development. However, its current focus on developing an advanced undersea deterrent, especially when viewed in the context of its SCS policy, is perhaps concerning, be it because of revisionist clinging to the restoration of Qing China’s spheres of influence, as a means to compensate for its inability to produce and indigenous long-range strategic bomber, or for the purpose of establishing itself as a regional hegemon, in any case, a credible and effective undersea deterrent arguably necessitates more forgiving geographical conditions, which in turn, necessitates a more assertive, revisionist policy in the SCS; the political ramifications of such a policy, in turn, necessitate an effective deterrent. It can perhaps be argued that China did not, until recently, possess the means to pursue such policies, and as such, did not place as much emphasis on its SSBN program.

PLAN Type 092 Changzheng 6 (Xia-class) in 2002 (navypedia.org)

There is evidence suggesting a revisionist flavour to China’s modernisation program, that China is either paving the way for, or already engaged in a transition to a more assertive strategy, which can be used as a tool for political coercion, first-strike capability, and perhaps even eventual nuclear parity with the United States and Russian Federation (Tkacik, 2014, p.162). Definite numbers for China’s delivery systems or warheads and concrete facts regarding their specifications are not easy to come by, and are mainly built on supposition and conjecture, and guesses at policy and doctrine tend to be made from the Western vantage point, where nuclear weapons exist purely as a deterrent. This may not be the case where Beijing is concerned, and it may be prudent not to make such assumptions when attempting to ascertain Chinese policy and capabilities.

China, today, with its economic girth, trade, and creditor status, is granted a degree of economic dominance reminiscent of the United States, post World War II, or the British Empire in the late 19th century. China looks increasingly like a potential future global hegemon (Tkacik, 2014 p.164), to this effect, Beijing has, according to Pacific Command Commander Admiral Timothy Keating, suggested that the Pacific be divided up into a Chinese sphere of influence in the fast, with China preparing for the possibility of conflict given American reluctance to cede even an inch of its domain (Tkacik, 2014 p165). This, and the scale of its modernisation program, are corroborated by the (relatively) dramatic increase in Chinese military expenditures, which by some estimates double or even triple the Russian Federation’s military budget. This behaviour can be interpreted as Beijing seeing itself as a great power and at least an equal to Washington.

There are, however, arguments that China’s arsenal expansion has historically been slow and minimal, and will continue to be (Tkacik, 2014, pp.166-7), but there are factors that existed before that do not now. The bipolar nature of the Cold War had relegated China, by no means the economic giant it is today, to second-rate power status, and various political, economic, industrial, and technological factors created a vast capabilities gap that the China of the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, and even ‘80s and ‘90s couldn’t hope to close. This is no longer the case. In terms of Purchasing Power Parity, China has already surpassed both the United States and the European Union in terms of sheer economic size. In absolute terms of nominal GDP, it is closer to the US than Imperial Japan was at the onset of the Second World War; it has, to a significant degree, modernised its infrastructure and continues to do so. Additionally, we are no longer in either a bipolar or even unipolar international system. The system is transitioning into a state of multipolarity, with China, a re-emerging Russia, and an emerging India on the periphery. Beijing is no longer a second-rate power; it is no longer relegated to having to pick a side, and the political implications of a potential breakout are less severe than they once were.

That considered, China finds itself in a position more similar to the Soviet Union in the early post-war period than to any other nuclear power; a rising superpower vying to hold its own and perhaps even displace the reigning hegemon, it is likely to follow a path similar to that of Moscow, rather than one similar to Paris or London, which had all but abandoned great power ambitions and could safely rely on NATO and America’s nuclear umbrella, or India which shows little, if any sign of possessing a revisionist worldview or hegemonic ambitions.

Findings.

Few details are known about China’s nuclear capabilities or doctrine; however, certain indicators can be examined as a whole to make some assumptions. It may have, once upon a time, held a doctrine of minimal deterrence with completely defensive intentions, but it is unclear if its historical minimal deterrent was such due to doctrinal and political constraints, or whether it had been due to geographical, industrial, economic, political, and military limitations. That China has in the past few decades, made great strides in relaxing, if not outright overcoming, in several cases, those limitations, and that the result is a relatively rapid modernisation and expansion of its arsenal suggests the latter. In several cases, these limitations still apply, notably the political ramifications of rapid expansion, its inability to develop an indigenous long-range strategic bomber program, and geographical constraints; however, it appears to be working to overcome these as well.

Beijing appears to have learnt from the mistakes of Imperial Japan and the Soviet Union, as it is not needlessly hasty to mount a hegemonic challenge; it is so slow, and arguably cautious in fact, that such ambitions can only be speculated, with a reasonable degree of confidence. Nevertheless, its present behaviour, especially in the context of its assertive policy in the SCS, and its international initiatives position it as a potential regional hegemon and the third horse in a tri-polar configuration of the international system, if not an outright hegemonic challenger to Washington, Overall, while admittedly speculative, its behaviour suggests a transition toward a more aggressive nuclear doctrine, reflecting its increasing capabilities, and quite possibly an eventual nuclear breakout. Its foreign policy, at the very least, appears to necessitate a more robust deterrent to avoid direct conflict.

That being said, there still appears to be a reactionary element to its nuclear modernisation and expansion, a less belligerent stance toward China on Washington’s part, or at least a less overt containment initiative may forestall the transition, though that may also be interpreted as a sign of weakness. Great powers don’t have the best historical record on keeping promises. There is a danger that the point of critical mass has already been crossed, and while this may not be reflected in terms of conventional and nuclear capabilities, Beijing is already in the process of asserting itself as a global power.

In a more general sense, it is difficult to determine whether doctrine is the limiting factor to a state’s nuclear capabilities or whether a state’s capabilities are what determine its doctrine and nuclear strategy. Either hypothesis depends heavily on the political context the state finds itself in; if there isn’t a political need for a large arsenal, there isn’t one, though this has yet to be tested in the context of a great power. Neither France for Britain are great power (anymore), neither has a large arsenal, both apply a doctrine of minimal deterrence, though in both cases, their indigenous deterrent is unnecessary given their inclusion under the NATO/US nuclear umbrella. As well, neither seems to have great power ambitions.

Both the Russian Federation and the United States have massive arsenals, full triads, and extensive capabilities, and these are the only states, at present, with the ability to maintain such arsenals. Their doctrines are most certainly shaped both by their capabilities and by each other’s. China is a particularly interesting test case because it couldn’t historically field an arsenal fir for much beyond minimal deterrence; its posture becomes more assertive as its capabilities improve, but the doctrine itself is vague and general enough to border on meaningless. I would posit that no state which has both the capability and political need for a large offensive arsenal and corresponding doctrine doesn’t have both in place. While states that are lacking one or the other have more defensive doctrines and corresponding arsenals. However, states with the means but not the need (France, Britain) have been reducing their stockpiles, while states that have the need (China, Pakistan, India) have the tendency to grow their arsenals as capabilities improve. I would posit, therefore, that while both the conventional wisdom and the alternate hypothesis have their merits. A more accurate conclusion would be that political need drives the development of nuclear capabilities, which in turn drives policy.

Policy implications and recommendations.

Beijing’s assertive policy in the South China Sea appears to be an attempt to create a more favourable geopolitical environment for itself. If it succeeds in securing unfettered access to the Pacific Ocean, or at least expanding its zone of influence to the first island chain, a breakout is likely. If a Chinese breakout is something to be prevented, then a policy of containment may be wise, and in order to do so, leveraging China’s dependence on the flow of goods, particularly energy through certain chokepoints (Malacca, Hormuz, Taiwan Straits) must be considered. A problem is that the current policy of dual-containment vis-à-vis Beijing and Moscow is counterproductive to this end. Forcing the two to deepen their ties and increasing pressure on Moscow’s interdependence in the energy sector with the EU may force it to turn eastwards, minimising Beijing’s vulnerability to blockades. As well, such a policy facilitates the transfer of advanced military technology from the Russian Federation to the People’s Republic of China; Su-30, S-300/400, the Liaoning and others have already been procured via Moscow. I would refer to Mackinder and Spykeman for more details on why pushing the two eastern powers together is probably short-sighted.

Building missile shields on China’s areas of interest is perhaps also a bad idea, which will only serve to prompt a security dilemma and arms race, this is especially dangerous as, unlike Moscow, Beijing is secretive about its modernisation and military development; we may not see the reaction to actions Beijing finds threatening until long after it is too late to reverse them. To that end, pushing Beijing’s buttons regarding Taiwan is very likely to trigger a response and may not be a prudent course of action. Ultimately, if containing China is a foreign policy priority, it may be prudent to avoid antagonising it outside of its SCS expansion. Preventing China from breaching the first island chain significantly reduces the efficacy of its SSBN program, and without a viable aerial arm to its triad, may prevent breakout altogether, at least until it develops an indigenous program. On the same token, driving a wedge between Beijing and Moscow can stand to work to slow the transfer of advanced military technology that would allow Beijing to fill gaps in its modernisation endeavour. The current China policy in Washington all but guarantees a Chinese breakout.

Bibliography

Banerjee, Major General Dipankar. “Addressing Nuclear Dangers: Confidence Building Between India-China-Pakistan.” India Review 9, no. 3 (2010): 345-63. doi:10.1080/14736489.2010.506352.

Yoshihara, Toshi, and James R. Holmes. “CHINA'S NEW UNDERSEA NUCLEAR DETERRENT Strategy, Doctrine, and Capabilities.” JFQ: Joint Force Quarterly no. 50 (Summer2008 2008): 31-38.Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Bleek, Philip C. 2004. “CHINA’S NUCLEAR POSTURE AT THE CROSSROADS: CREDIBLE MINIMUM VERSUS LIMITED DETERRENCE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ENGAGEMENT.” Kennedy School Review 5, 1-12. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Weitz, Richard. 2015. “New Advances Challenge Old Truths About China’s Nuclear Posture.” World Politics Review (Selective Content) 1. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Tkacik, Michael. 2014. “Chinese Nuclear Weapons Enhancements – Implications for Chinese Employment Policy.” Defence Studies 14, no. 2: 161-191. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Simon, D.F. 1988. “The Chinese Army after Mao by Ellis Joffe” Bulletin Of The Atomic Scientists 44, no. 5: 46. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Kristensen, Hans M., and Robert S. Norris. 2015. “Chinese nuclear forces, 2015” Bulletin Of The Atomic Scientists 71, no. 4: 77-84. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Kristensen, Hans M., and Robert S. Norris. 2006. “Chinese nuclear forces, 2006.” Bulletin Of The Atomic Scientists 62, no. 3: 60-63. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Norris, Robert S., and Hans M. Kristensen. 2010. “Global nuclear weapons inventories, 1945–2010." Bulletin Of The Atomic Scientists 66, no. 4: 77-83. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Norris, Robert S., and Hans M. Kristensen. 2008. “Chinese nuclear forces, 2008.” Bulletin Of The Atomic Scientists 64, no. 3: 42-44.Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Kristensen, Hans M., and Robert S. Norris. 2013. “Chinese nuclear forces, 2013.” Bulletin Of The Atomic Scientists 69, no. 6: 79-85.Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Babiarz, Renny. 2015. The people’s nuclear weapon: Strategic culture and the development of china’s nuclear weapons program. Comparative Strategy 34 (5) (Nov): 422-46.

Fieldhouse, Richard. 1991. China’s mixed signals on nuclear weapons. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 47 (4) (05): 37-42.

Goldstein, Lyle J. 2003. When China was a ‘rogue state’: The impact of China’s nuclear weapons program on US-China relations during the 1960s. Journal of Contemporary China 12 (37) (11): 739.

Lewis, John W., and Xue Litai. 2012. Making China’s nuclear war plan. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 68 (5) (09): 45-65.